“The Lost Voice,” a new two-minute short film from Apple, directed by Taika Waititi. A richly told story about a single, powerful accessibility feature.

“The Lost Voice,” a new two-minute short film from Apple, directed by Taika Waititi. A richly told story about a single, powerful accessibility feature.

From Nick McDonell’s new book “Quiet Street: On American Privilege”:

Such skills arose not from any extraordinary talent or discipline but from the enormous resources invested in each child. And though I have here emphasized traditionally highbrow skills, we were groomed to be comfortable at every level of culture, in every room—to appreciate Taylor Swift as well as Tchaikovsky, to make small talk with the custodian as well as the senator. The deeper lessons were confidence, poise in any context, what sociologist Shamus Rahman Khan calls ease. Old-fashioned exclusionary markers could in fact be a liability, in the same way an all-white classroom was. All the world was ours not because of what we excluded or inherited but because of our open-minded good manners and how hard we worked—which, all agreed, was very hard indeed. This superficial meritocracy masked, especially to ourselves, a profound entitlement.

Reading McDonell’s slim memoir brought to mind one of my all-time favorite works of nonfiction, “Lost Property: Memoirs and Confessions of a Bad Boy”, Ben Sonnenberg’s high-culture self-flaying that begins this way: “I was a Collectors’ Child.”

The authors are very different people (as were their parents, consequentially), but they share an interest in examining what privilege has done to them. I grabbed “Lost Property” from the shelf and found a squiggle next to this passage of homecoming.

For once in my life I liked going to 19 Gramercy Park, going there with my wife and baby daughter. My mother and father loved Alice, and I loved showing Alice where I’d grown up and showing off to the servants. One afternoon, watching Susy, on the needle-point rug, in the paneled library, I rememberd how once at a dealer’s, a decripit old collector came, with his young wife and new baby, to inspect a white-figure wine jug of the fourth century B.C. The baby pulled at something, the lekythos nearly fell, and from the way the collector looked, I knew if he had had to choose between the vase and his baby, the baby would be dead. I’m not like that, thank goodness, I thought, watching Susy on the rug, watching my parents watching me, turning my foot from side to side, catching the light on my shoe.

Fantastic, instructive book: “Scaling People: Tactics for Management and Company Building," by Claire Hughes Johnson. She’s a real-deal practitioner, and many of these lessons trace back to her infrastructural work at Stripe, which she helped grow. The book’s focus is on the operating principles to create within an organization — “how to create and embed the systems that help build a company you can be proud of.” (Since her primary reference point is Stripe, having a “writing culture” plays a role.)

Prompted by this Jarrett Fuller post, I scooped up and quickly read “Two-Dimensional Man: A Graphic Memoir” by Paul Sahre. Funny, poignant at times — a great read for any creator. The memoir includes a good deal of striking work shown between prose pages, including several book covers I’ve long admired. You can get a good sense of Sahre’s sensibility by knowing that when he officialy launched his solo design business — the Office of Paul Sahre — he embraced its unintended acronym: O.O.P.S.

“‘My Body Is a Clock’: The Private Life of Chronic Care,” a moving and arresting photo series + essay by Sara J. Winston:

Every 28 days, I point the camera toward myself to document my illness and care. I have used my time as a patient in the infusion suite, a place where I sometimes feel powerless, to reclaim my autonomy as an artist and photographer.

One of the best books I’ve read this year: “The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of Cancer," by Siddhartha Mukherjee. What an immensely impressive person: a first-class physician-scientist who’s also an exceptional storyteller with a deeply literary sensibility.

In love with just about every one of these Janet Hansen-designed book covers.

After learning that Cormac McCarthy had died, I went back to my squiggled-up copy of “Suttree,” which of all his novels is the one that moved me most. I first read it in the fall of 2002, right after being whalloped by “Blood Meridian,” and it’s never left me.

Here’s the title character, assessing the unforgettable Gene Harrogate, comically pitiable yet not only that:

Suttree looked at him. He was not lovable. This adenoidal leptosome that crouched above his bed like a wizened bird, his razorous shoulderblades, jutting in the thin cloth of his striped shirt. Sly, ratfaced, a convicted pervert of a botanical bent. Who would do worse when in the world again. Bet on it. But something in him so transparent, something vulnerable. As he looked back at Suttree with his almost witless equanimity his naked face was suddenly taken away in darkness.

Later, McCarthy writes of Suttree dreaming, in a passage rich with equisitely chosen nouns and verbs:

Down the nightworld of his starved mind cool scarves of fishes went veering, winnowing the salt shot that rose columnar toward rifts in the ice overhead. Sinking in a cold jade sea where bubbles shuttled toward the polar sun. Shoals of char ribboned off brightly and the ocean swell heaved with the world’s turning and he could see the sun go bleared and fade beyond the windswept panes of ice. Under a waste more mute than the moon’s face, where alabaster seabears cruise the salt and icegreen deeps.

“A. G. Sulzberger on the Battles Within and Against the New York Times”: I was very impressed with Sulzberger during this extended conversation with David Remnick. Brought to mind the scenes in the Ben Smith book noted below, in which the NYT transforms from an org that appears to seek advice from the likes of BuzzFeed to one that builds on its ‘legacy’ status, rising confidently and profitably as that site falters.

I found a good amount of Ben Smith’s briskly paced new book “Traffic: Genius, Rivalry, and Delusion in the Billion-Dollar Race to Go Viral” disheartening, in considering the vast amount of energy often bright (not always cynical) people were putting into voraciously attracting and retaining eyeballs with puffs of briefly entertaining trifles (some of which I also hungrily clicked on, and will do so again). Smith shares a number of interesting stories, both from his time observing and then working from within this particular type of machine. This was my favorite small detail, in which Smith recalls what happened after he joined the rising BuzzFeed media empire (after first turning the offer down) and pressed publish on his debut piece, “Welcome to BuzzFeed Politics,” setting the tone for a significant new social news organiziation:

Then I went to check the page: it was nearly illegible, the lines almost on top of each other. BuzzFeed had never before published a full paragraph.

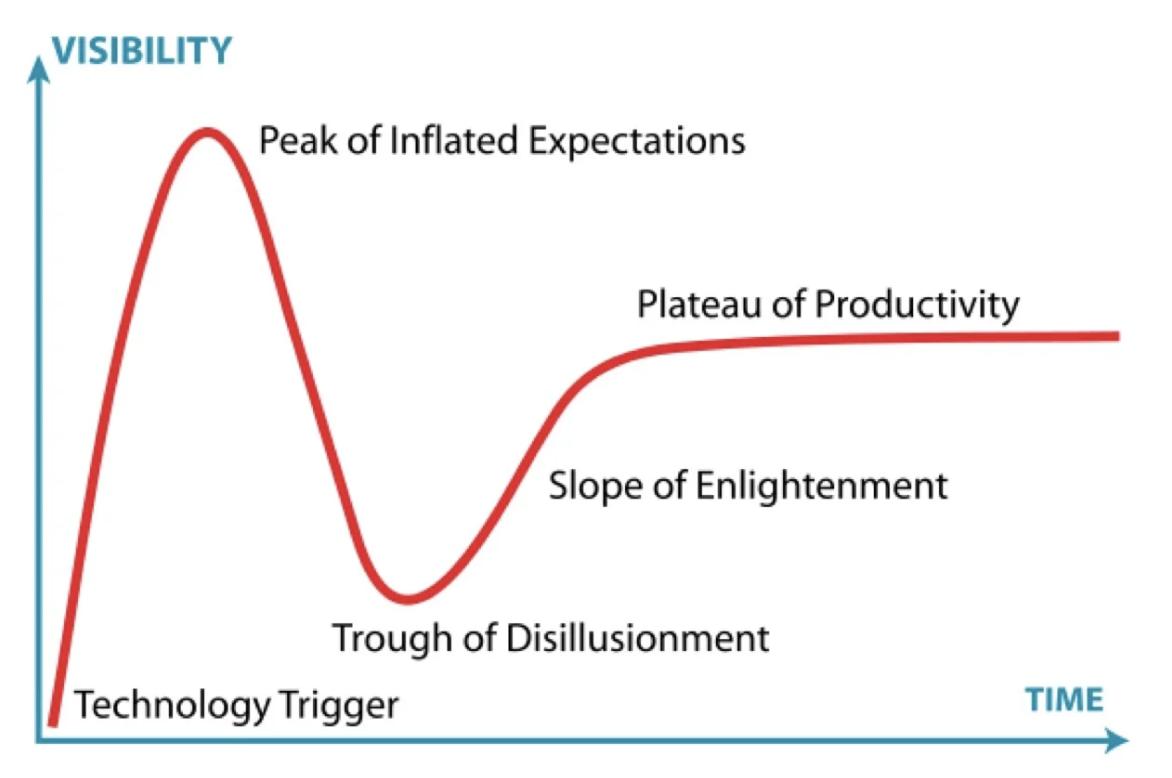

I feel behind not having heard of the Gartner Hype Cycle, which charts the rise, fall, and settling-in adoption of emerging technologies. One of the hosts of the “People vs. Algorithms” podcast referred to it in a recent conversation about ChatGPT. Seems apt. We might be getting closer to the trough of disillusionment.

Our little group paused in front of “Woman in Blue Reading a Letter,” and it was so beautiful that my heart almost stopped. The paint keeps to a narrow range of hues: The wall is off-white with blue undertones; the large map of the regions of Holland and West Friesland is light brown with a hint of green; the two chairs on either side of the woman have glimmering brass tacks that hold their deep blue upholstery in place. One chair is larger than the other, closer to us while the other is farther away, and between them is the space in which the woman stands. She is clad in a top of blue and a skirt of dark olive. All the colors are so muted, it is as though they are remembered rather than painted.

From Teju Cole’s perceptive essay “Seeing Beyond the Beauty of a Vermeer,” published in The New York Times Magazine.

“A Korean American connects her past and future through photography”: A lovely first-person piece by Arin Yoon, published by NPR. Beautiful work.

I recently finished and enjoyed Frank Rose’s “The Sea We Swim In: How Stories Work in a Data-Driven World,” which focuses on the power of narrative, particularly for brands. There’s a nice collection of what might be called ancillary brand communications initiatives, including MyJohnDeere, described as an online “information exchange for farmers” — offered as a supplement, say, to the company’s digital brochureware meant to advance the sales pipeline.

It adds up to a radical reenvisioning of what John Deere is and why it exists. As Sunil Gupta of Harvard Business School put it, the real question is, “What business are you in?”

Rose quotes Gupta at length:

For the longest time, if you asked John Deere this question, the company would say they are in the business of producing farm equipment … but if you look at it from a slightly different angle, the reason why a farmer buys John Deere equipment is to have better productivity on the farm. Slowly, John Deere recognized that they are not in the business of producing tractors and trailers, but instead, are in the business of farm management to help the farmers increase the productivity on their farms.

Fantastic interview on the Time Sensitive podcast with a writer I admire: “Jelani Cobb on 50 Years of Hip-Hop and the Future of Journalism.”

I have a few minor quibbles with Cormac McCarthy’s recent sharp and memorable novel “Stella Maris”, but listening to the audio version — two characters in dialogue throughout — was the ideal way to take it in.

Thought-provoking piece by Ted Chiang: “Will A.I. Become the New McKinsey?”

We modern-day humans tend to exaggerate our differences. The results of such exaggerations are often catastrophic.

— From “The Dawn of Everything,” by David Graeber and David Wengrow

“The New New Reading Environment” — A sharp survey from the editors at n+1.

“How Much Does ‘Nothing’ Weigh?” — A fantastic, strikingly photographed feature in Scientific American. The experiment aiming to measure the void of empty space will be conducted in an abandoned mine in Sardinia.